The Queen’s English

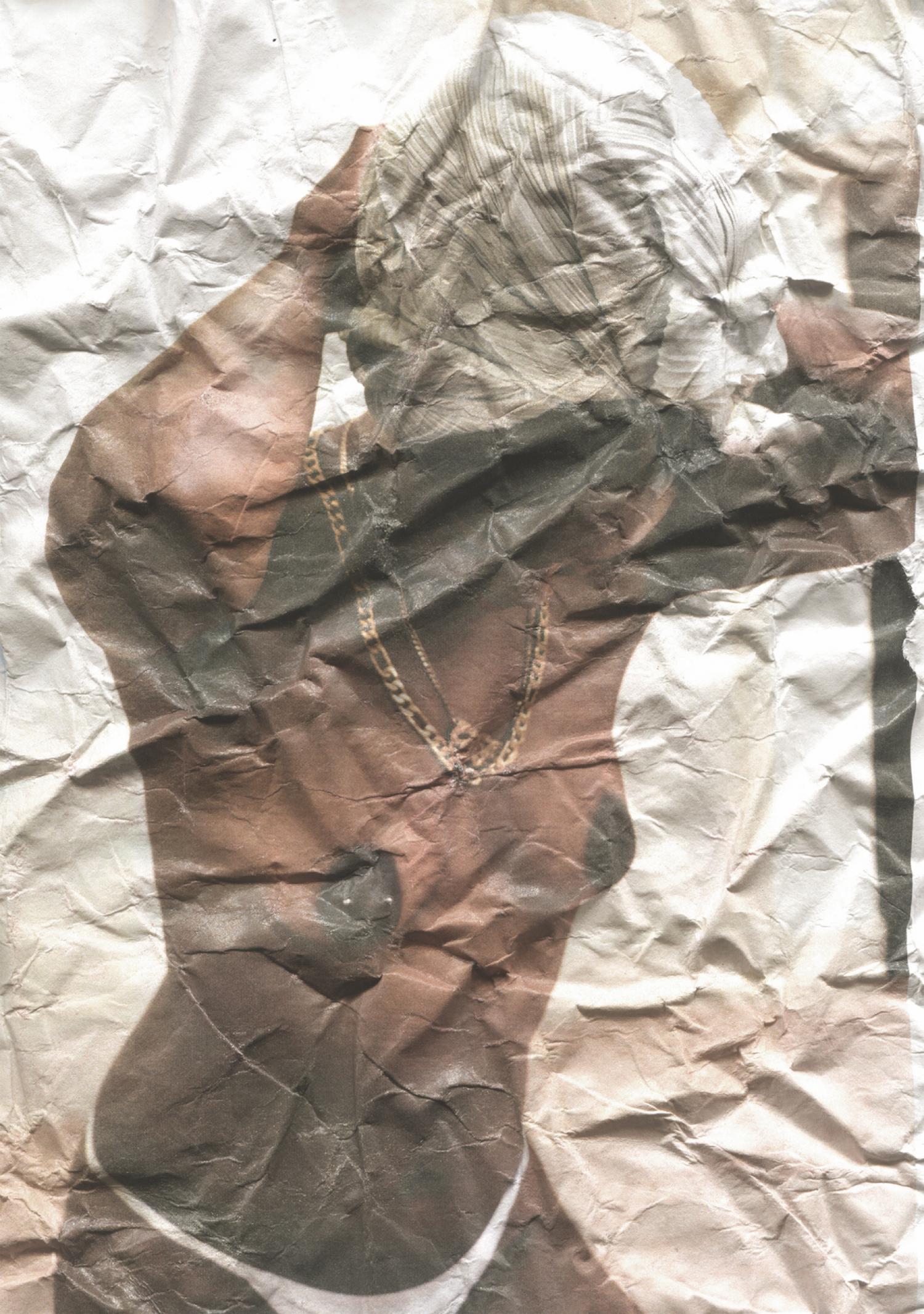

At the entrance of The Queen’s English (2014) by Martine Syms, there is a C-stand. A large vinyl print hangs from this stand. The person in the image printed on the vinyl is looking directly into the camera, which is to say, into the eyes of the photographer or the viewer. They are Black.I am using the term Black rather than African American/Canadian or West Indian American/Canadian for two reasons. Firstly, it is the term that Martine Syms uses. Secondly, because the national-geographic terms never apply to all authors whose works have been influential for this essay, including Martinician Édouard Glissant and Jamaican Sylvia Wynter. Alexander G. Weheliye, Professor of African American Studies at Northwestern University in Chicago, notes, “The theoretical and methodological protocols of Black studies have always been global in their reach, because they provide detailed explanations of how techniques of domination, dispossession, expropriation, exploitation, and violence are predicated upon the hierarchical ordering of racial, gender, sexual, economic, religious, and national differences.” Habeas Viscus (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 5.The blown-up image is criss-crossed by the kind of folds that occur when a piece of paper or a photograph is carried around in a pocket for a long time. The person in the picture wears street clothing: jeans, a jean jacket, a white T-shirt. Their left leg is set in front of the right one; they are in movement, about to take a step forwards. They carry a skateboard under their right arm. There is something hanging from their right shoulder, which leads over their chest in a diagonal line, visually disappearing under their left armpit, like a ring. With their left hand, they hold something in front of their face, thus covering up the lower half of it. The viewer is unable to see the person’s nose or mouth, only the eyes staring back at them are visible. Due to the magnification of the image, the object held by the person is not clearly recognizable. It might be another photograph that they are showing the camera, or a hip flask from which they are drinking, or something they are using to amplify their voice, like a microphone or megaphone. A slightly taller Black woman is looking over their right shoulder from behind, and she too looks directly into the camera, as she wraps a white blanket around her body. Behind these two, I can recognize a blurry crowd of people, while what looks like a flag alongside something round, perhaps a balloon, hovers above their heads. The perspective in which these elements are arranged within the picture, in a line of flight towards the background, indicates that the crowd is walking down a street, towards the camera. A series of buildings with glass facades lines this street, as they might in the downtown business district of any North American, Asian, or cosmopolitan European city. The photograph itself provides no exact indication of when and where this event occurred.

I initially took up the research on The Queen’s English because, as a publisher, I was interested in finding out more about Black feminist literary production in North America during the 1970s and 1980s. I ended up on page 123 of Robyn Maynard’s book, where I read that in Hamilton, Ontario, in 2003, Chevranna Abdi, a 26-year-old Black transgender woman, was handcuffed and dragged down seven flights of stairs by law enforcement officers.Robyn Maynard, Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present (Halifax: Fernwood, 2017), 123–24.By the time they reached the lobby on the main floor, she was not breathing. She died in police custody. Her death was ruled accidental by the Special Investigations Unit, and none of the officers, who claimed that they were fatigued after carrying her down the stairs, got charged.The Special Investigations Unit (SIU) is a civilian law enforcement agency independent of the police that conducts investigations of incidents involving the police that have resulted in death, serious injury, or allegations of sexual assault.The media coverage attributed Abdi’s death to her use of drugs, as well as to her HIV status and being transgender. As if the sheer violence of her death would not be atrocious enough, this violence is doubled up in its recounting. Considering this, what does it mean to retell this story here? Is it a story at all? Does it say anything about who Chevranna Abdi was? There is no mention of what she was doing that day prior to the arrival of the police, and the days before that day, whom she met, and where she went. To live means to be in relation to people, places, and things. Reducing Abdi’s story to retelling the facts of what happened between the upper and the ground floor means not only to reduce a life to its last moments, but also to reduce the story of this life to a script according to the measurement of the facts that feed it, which are seemingly self-evident. Both the reader and who is telling it have functions in this reproduction.For how story can work to disrupt the script, see Aimee Meredith Cox, Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).The latter is in this case me, a white European cis woman.

This essay therefore interrogates its own discursive reproduction, which shares its script with technologies of imaging that are not exclusively applied in the visual arts. These technologies reproduce a white prototypicality, and serve to reduce the social space of people of colour to body-as-site. Black feminist opacity, then, as I see it enacted in Martine Syms’s work, disables this reduction as a refusal that relates.

Syms describes the photograph in the vinyl print in opaque terms, as “an archival photograph of a protest.”Martine Syms, email correspondence with the author.It could stem from her great-aunt’s photo collection that she inherited and often uses in her work. Or it could be a part of a public archive. Although there exists no systematic data collection in Canada on police violence that is based on gender and sexuality, the Toronto Police Service, in the period between 2008 and mid-2011, has amassed 1.25 million contact cards collecting personal information of randomly stopped citizens. In this massive database, entries of young Black men are registered at a rate of 3.4 times that of their population in the city.Maynard, Policing Black Lives, 89.The Toronto Police cards (named Field Information Reports, or, most recently, Community Engagement Reports) catalogue bodily features such as race, gender, height, weight, and eye colour, which are later input to a computer database. If Shoshana Magnet defines biometrics as the application of statistical techniques in the science of using biological information for identification, then carding is a form of biometrics.Shoshana Magnet, When Biometrics Fail: Gender, Race, and the Technology of Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 8.It is what Simone Browne names “a technology of measuring the living body.”Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 109.Her dissertation, submitted to the University of Toronto in 2007, investigated the identity industrial complex that complements the prison industrial complex, using Canada’s permanent resident (PR) card as a site in which technologies of surveillance and border control rely on the notion that “the body will reveal the truth about a person’s identity despite the subject’s claims.”Simone Arlene Browne, “Trusted Travellers: The Identity-Industrial Complex, Race and Canada’s Permanent Resident Card” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2007).The effects of this biocentric logic of recognition or misrecognition are diametrical for those arrested by police versus the holders of, or denied applicants to, PR cards. What they have in common is that they serve as tools to reduce personhood in a two-step program: from a person to a material, physical body, and from this physical body to a body of data. Self-evidence is generated by the feeding of data to algorithms, enabling “a mode of authenticity shaped to artificially intelligent truths,” as media theorist Wendy Chun observes. This mode of authenticity results from network science’s exploration, prediction, and exploitation of what it understands to be “the rhythms of life.”Albert-László Barabási, Bursts: The Hidden Patterns of Everything We Do (New York: Dutton, 2010), 11.Biometric technologies include facial recognition, iris and retinal scans, hand geometry, fingerprint templates, vascular patterns, DNA scans, gait, and other types of kinesthetic recognition scanners. These technologies do not recognize the living body in front of them, but apply algorithms that make decisions based on measuring the life before them against the facts that feed them.

As Maynard’s research shows, Black women and transgender people are not exempt from the violence of stereotypical hyper-representation, while at the same time being rendered invisible by so-called technologies of recognition that are not made to recognize. But the decision-making processes of the algorithms that feed these technologies are steered by a finite list of instructions calculating a function, that is, by a script written in binary code. This script depends on the “natural” biocentricity of facts as epistemologically legitimated by the Darwinian narrative of life as purely biological being.Sylvia Wynter, “Beyond the Word of Man: Glissant and the New Discourse of the Antilles,” World Literature Today 63, no. 4 (Autumn, 1989): 637–48.Algorithms are not neutral. The white maleness of the tech industry absorbs post-internet art or the inverse. It makes the current Berlin Biennale appear to be separate from the last one, rather than relating the two. This binary script is historically engineered by that which Hortense Spillers calls “the symbolic order called American Grammar.”Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer, 1987): 64–81.By that which Sylvia Wynter calls “the sociogenic principle.”Browne, Dark Matters, 11. See also Sylvia Wynter, “Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, Identity, the Puzzle of Conscious Experience, and What It Is Like to Be ‘Black,’” in National Identities and Socio-Politial Changes in Latin America, ed. Mercedes Durán-Cogan and Antonio Gómez-Moriana, vol. 23, Hispanic Issues (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).By that which Katherine McKittrick calls “the mathematics of the unliving.”Katherine McKittrick, “Mathematics Black Life,” The Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 16–28.By that which Édouard Glissant calls “transparency.”Édouard Glissant, “Transparency and Opacity,” in Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1997), 111–20.And by that which Syms calls The Queen’s English. These names are not the same, but they are related. Together, they name the symbolic and organizational framework of a social order or network that defines what is and what is not a part of life. This order is biometrically stabilized by measuring each subject against scripted, self-evident facts.

Dark Sousveillance

This racist symbolic framework is nothing new. Nehal El-Hadi reminds of Christina Sharpe’s assessment that its virtual reproduction only exposes it as already virtual construction in real life.Nehal El-Hadi, “Death Undone,” The New Inquiry, May 2, 2017, quoting Christina Elizabeth Sharpe, “Racialized Fantasies on the Internet,” Signs 24, no. 4 (Summer, 1999): 1090.Browne, then, locating the conditions of Blackness as a key site through which surveillance is practiced, narrated, and resisted, traces the socially produced contrast of the security of light versus the danger of darkness. From the panopticon of the slaveship, via eighteenth-century lantern laws in New York City that forbade Black and Indigenous people to go out without a lantern after sunset, to biometric branding, this contrast in effect produces a white prototypicality against which the depicted or documented subject is measured. This white prototypicality remains inherent to any image technology today. A simple example for this is the significantly higher Fail to Enroll Rates for darker-skinned users of face-focus-recognition tools on cell phone cameras. Not only (in)visibilities but (im)materialities are produced by this diachronic bifurcation of contrast, including of physical bodies. In addition to law enforcement, biometric technologies are used today by most sovereign nation-states to control people’s movements across borders via their passports, where the invisibility caused by Fail to Enroll Rates can decide over the course of someone’s life. Biometric technologies are also integrated into the surveillance contexts of corporate office buildings, gas stations, parking lots, prisons, refugee camps, residential streets, schools, social media (tagging), supermarkets, universities, and so on. Browne therefore delineates “dark sousveillance” as a counterstrategy that takes up Blackness as a lived materiality, which is “hopeful for another way of being.” Dark sousveillance is what former slave Sam performs by turning up the whites of his eyes when being addressed. It is also the capacity to distort and interfere with algorithms.Browne, Dark Matters, 21, 164.It troubles and expands the concept of (white) sousveillance as introduced by Steve Mann et al.Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman, “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments,” Surveillance and Society 1, no. 3 (2003): 331–55.In this way, dark sousveillance offers an analytical frame through which a subject can stare back at the biocentric identity that seeks to govern Black lives, and “understand the network outside if itself.”

Informatic Opacity

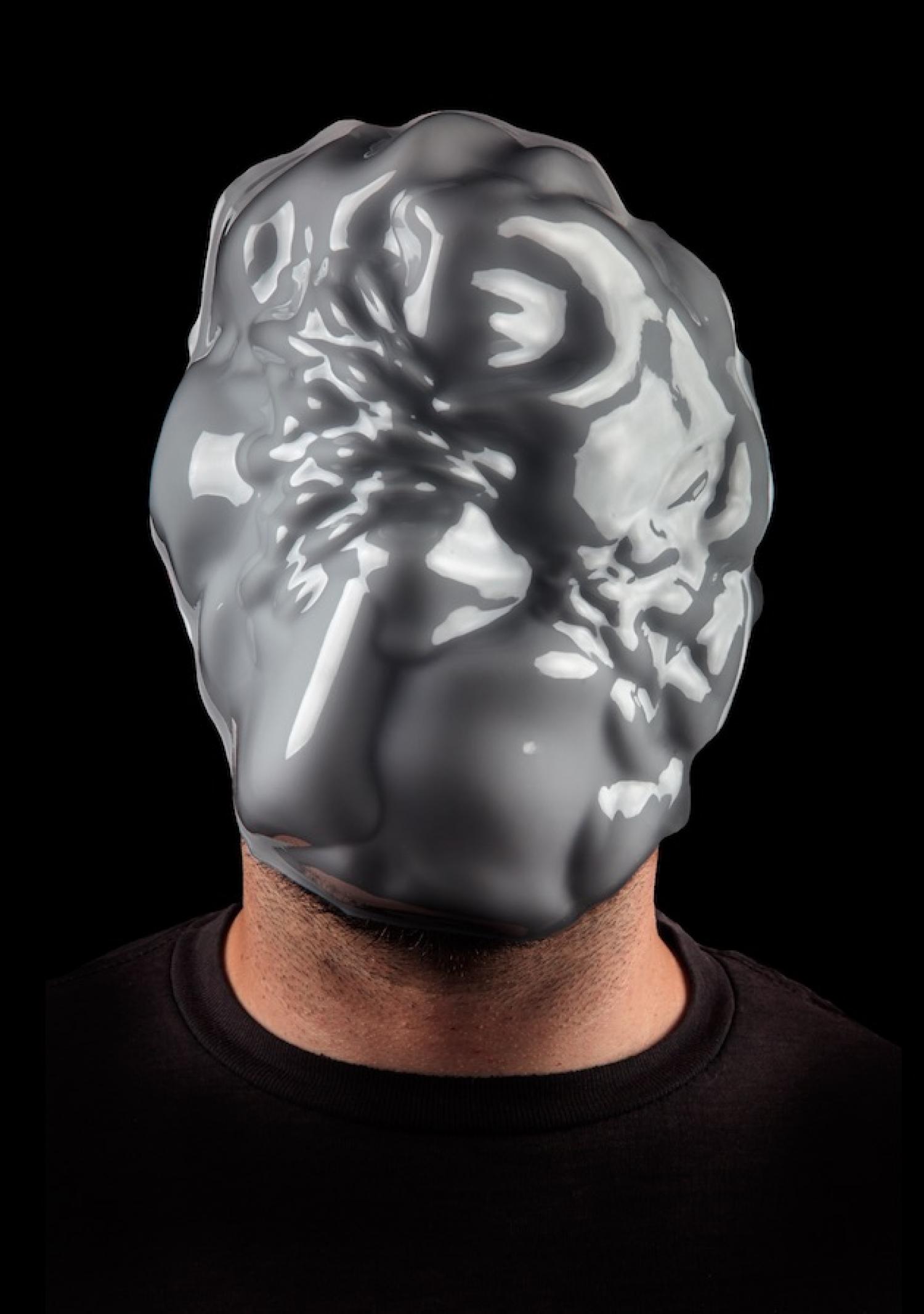

Rather than further adding to the universal network or database, actors in the fields of political thought, media studies, queer theory, and art criticism today increasingly employ what artist and writer Zach Blas sums up as “informatic opacity.” Basing this concept on the writings of Glissant, one of Blas’s most recent definitions of informatic opacity describes it as “a paradigmatic concept to pit against the universal standards of informatic identification,” as “a practice of anti-standardization at the global, technical scale,” and as “a kind of ontological tactics of and for the minoritarian.”Zach Blas, “Informatic Opacity,” Posthuman Glossary, ed. Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova (London: Bloomsburry), 198–99.As an artist, Blas has produced a body of work entitled Facial Weaponization Suite (2011–2014), in which he deploys biometric data in the construction of abstract masks.

According to Blas, the wearing of these masks enables at once an invisibility towards surveillance technologies, and the experience of an anonymous collectivity among the wearers of these masks. As an artist, Blas did collaborate with Ricardo Dominguez on a mask for an exhibition at the MUAC in Mexico City dedicated to the complex web of approaches that underlie racism. Though clearly based on the work of Black Martinician writer and poet Glissant, in his first comprehensive introductory article into the concept of informatic opacity in Camera Obscura magazine in 2016, Blas situated this concept along the writings of mainly white male authors from the global North, including Alexander R. Galloway, Eugene Thacker, McKenzie Wark, The Invisible Committee, Nicholas de Villiers, and Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri.Zach Blas, “Opacities: An Introduction,” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 31, no. 2(92) (2016): 148–53.These writings investigate ideas of opacity, invisibility, and non-existence under the conditions of mass surveillance. Therefore, Blas sees informatic opacity to be “in contrast with identity politics’ claim to visibility as a political platform.”Blas, “Opacities,” 150.However, the majority of these writers are participants in a predominantly white discourse that is US- and Western European–centric, which conditions the standard measurements and prototypicalities of self-evidence in the context of contemporary art.See, e.g., A Decade of Arts Engagement: Findings from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, 2002–2012: National Endowment for the Arts Research Report #58, Washington: National Endowment for the Arts, 2015. The 2015 Art Museum Diversity Survey by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation notes, “Among its chief findings, the survey documented a significant movement toward gender equality in art museums. Women now comprise some 60 percent of museum staffs, with a preponderance of women in the curatorial, conservation and education roles that can be a pipeline toward leadership positions. The survey found no such pipeline toward leadership among staff from historically underrepresented minorities. Although 28 percent of museum staffs are from minority backgrounds, the great majority of these workers are concentrated in security, facilities, finance and human resources jobs. Among museum curators, conservators, educators and leaders, only four percent are African American and three percent Hispanic.” Accessed February 28, 2017, https://aamd.org/our-members/from-the-field/art-museum-diversity-survey. And in Canada: Alison Cooley, Amy Luo, and Caoimhe Morgan-Feir, “Canada’s Galleries Fall Short: The Not-So Great White North,” Canadian Art (April 21, 2015), http://canadianart.ca/features/canadas-galleries-fall-short-the-not-so-great-white-north; Michael Maranda, “Hard Numbers: A Study on Diversity in Canada’s Galleries,” Canadian Art (April 5, 2017), http://canadianart.ca/features/art-leadership-diversity.Alongside the statistical data listed in the preceding note, this observation can be supported by the fact that Syms’s 2017 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City as a part of its Projects series—according to the institution’s online exhibition archive—is the second solo show by a Black female artist in the institution’s history after Lorna Simpson’s 1990 show in the same series, followed by Adrian Piper’s retrospective this year.

According to Blas, the wearing of these masks enables at once an invisibility towards surveillance technologies, and the experience of an anonymous collectivity among the wearers of these masks. As an artist, Blas did collaborate with Ricardo Dominguez on a mask for an exhibition at the MUAC in Mexico City dedicated to the complex web of approaches that underlie racism. Though clearly based on the work of Black Martinician writer and poet Glissant, in his first comprehensive introductory article into the concept of informatic opacity in Camera Obscura magazine in 2016, Blas situated this concept along the writings of mainly white male authors from the global North, including Alexander R. Galloway, Eugene Thacker, McKenzie Wark, The Invisible Committee, Nicholas de Villiers, and Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri.Zach Blas, “Opacities: An Introduction,” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 31, no. 2(92) (2016): 148–53.These writings investigate ideas of opacity, invisibility, and non-existence under the conditions of mass surveillance. Therefore, Blas sees informatic opacity to be “in contrast with identity politics’ claim to visibility as a political platform.”Blas, “Opacities,” 150.However, the majority of these writers are participants in a predominantly white discourse that is US- and Western European–centric, which conditions the standard measurements and prototypicalities of self-evidence in the context of contemporary art.See, e.g., A Decade of Arts Engagement: Findings from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, 2002–2012: National Endowment for the Arts Research Report #58, Washington: National Endowment for the Arts, 2015. The 2015 Art Museum Diversity Survey by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation notes, “Among its chief findings, the survey documented a significant movement toward gender equality in art museums. Women now comprise some 60 percent of museum staffs, with a preponderance of women in the curatorial, conservation and education roles that can be a pipeline toward leadership positions. The survey found no such pipeline toward leadership among staff from historically underrepresented minorities. Although 28 percent of museum staffs are from minority backgrounds, the great majority of these workers are concentrated in security, facilities, finance and human resources jobs. Among museum curators, conservators, educators and leaders, only four percent are African American and three percent Hispanic.” Accessed February 28, 2017, https://aamd.org/our-members/from-the-field/art-museum-diversity-survey. And in Canada: Alison Cooley, Amy Luo, and Caoimhe Morgan-Feir, “Canada’s Galleries Fall Short: The Not-So Great White North,” Canadian Art (April 21, 2015), http://canadianart.ca/features/canadas-galleries-fall-short-the-not-so-great-white-north; Michael Maranda, “Hard Numbers: A Study on Diversity in Canada’s Galleries,” Canadian Art (April 5, 2017), http://canadianart.ca/features/art-leadership-diversity.Alongside the statistical data listed in the preceding note, this observation can be supported by the fact that Syms’s 2017 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City as a part of its Projects series—according to the institution’s online exhibition archive—is the second solo show by a Black female artist in the institution’s history after Lorna Simpson’s 1990 show in the same series, followed by Adrian Piper’s retrospective this year.

The Antillean island of Martinique, where Glissant is from, is neighbour to the independent republic of Dominica that lends its name to Syms’s imprint. Syms’s work eludes Blas, while he mentions Hito Steyerl’s How Not to Be Seen (2013). Instead of Browne’s dark sousveillance, Blas references Swiss curator Ulrich Loock’s essay on opacity in Frieze magazine. Glissant, then, brought on opacity to get “beyond the word of [be it Fanon’s or Foucault’s] Man,” that is the transparent, heteropatriarchal, and exploitative logic of modern humanist thought imposed by settler colonialism, against the prototypical facts of which his subjectivity was measured.Wynter, “Beyond the Word of Man.”Black women are silenced in either case. It is for exactly such reasons that #citeblackwomen was initiated. The Camera Obscura article is certainly not representative of Blas’s entire work in the field of informatic opacity, which in the past paid extensive reference for instance to the work of Browne and Magnet.See, e.g., Zach Blas, “Escaping the Face: Biometric Facial Recognition and the Facial Weaponization Suite,” NMC Media-N, Journal of the New Media Caucus 9, no. 2 (Summer 2013), http://median.newmediacaucus.org/caa-conference-edition-2013/escaping-the-face-biometric-facial-recognition-and-the-facial-weaponization-suite/ as well as his interview with Simone Browne, “Beyond the Internet and All Control Diagrams,” The New Inquiry, January 24, 2017, https://thenewinquiry.com/beyond-the-internet-and-all-control-diagrams.The article is rather a kind of summary of Blas’s earlier work. It appears as an introduction into this work for a contemporary art audience, by skipping some of its foundational references. It is this scripted discursive function, and the edits that this script brings with it, that points to the extent to which not only the biometrically based image technology of contemporary art but also its discursive framework reduce the participation of people of colour and reproduce a white prototypicality.

Black Feminist Opacity

But a reproduction is never identical with what it represents. The person in the image printed on the large vinyl that is hanging from the C-stand is looking directly into the camera, which is to say, into the eyes of the photographer or the viewer. They acknowledge a relationship while simultaneously transforming it. On a film set, the C-stand is the technology that directs or deflects, intensifies and filters light. The image presented on the C-stand has been produced by the framework of contemporary art as much as it is supported by it. At the same time, Syms’s C-stand intervenes in the optical path of illumination and enlightenment, deflects and redirects this light. It resets its own framework. It functions as an opacity that enables “the understanding that it is impossible to reduce anyone, no matter who, to a truth they would not have generated on their own.”Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 194.

The title of this essay features the second half of a sentence found in the introduction to a 2004 report on racial profiling written by Maureen J. Brown and commissioned by the African Canadian Community Coalition on Racial Profiling. The full sentence reads, “We have documented the phenomenon of racial profiling because as a society we can’t manage what we can’t measure, nor can we deny what we have not documented.”Maureen J. Brown, “In Their Own Voices: African Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area Share Experiences of Police Profiling,” commissioned by the African Canadian Community Coalition on Racial Profiling, March 2004 (quoted by Maynard, Policing Black Lives, 124).In order to find a way to shift the biocentric frame, and to hack the algorithmic scripts of the network, Black feminist opacity acknowledges the first half of this sentence, but it emphasizes the latter. This does not mean that it situates opacity in contrast with identity politics’ claim to visibility as a political platform, which is what informatic opacity does as per Blas’s suggestion. In The Queen’s English, which arises from the circulation of information in Black feminist communities, visibility is that which opacity constructs. It is Evelynn Hammonds’s Black (w)holes, which can be detected by their effects on the place where they are located.Evelynn Hammonds, “Black (W)holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality,” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 6.2+3 (1994): 126–45.In this regard, what does it mean that the authors of the works I consulted most substantially for this article have lived in Toronto or Canada for significant parts of their lives? Perhaps this speaks to my sorting of the data, which is the hominid activity that is necessitated by the capturing of data through machines. But it also points towards a place. This place shapes a shared space that is not anonymous. Rather, in McKittrick’s words, it is a “Black knowledge formation that, while certainly embodied, is not reduced to the biologic.”Katherine McKittrick, “Diachronic Loops/Deadweight Tonnage/Bad Made Measure,” cultural geographies 23, no. 1 (2016): 4.Also, for Glissant, opacity is “that which cannot be reduced” (to the unicity of the transparent).Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 191.In this sense, it is a refusal. But it is a refusal that relates.

In reproduction, there is a gap. Between the original and its reproduction, between story and script, between material body and body of data, between depicted subject and viewer, between past and future. This gap eludes the measurements of time and space. Materially, it is the images’ folds that underline its own factuality over the facts depicted by it. In this gap, subjecthood can never be entirely understood. It exceeds the frame of its capture rather than opposing it as an anti or counter. What is at stake for Black feminist opacity is to inhabit this gap not as difference, but as opacity. A minority is measured against a majority. Measuring against produces difference. To relate enables co-existence and convergence, the weaving of a fabric instead of the establishment of an order. Black feminist opacity relates, it does not measure. It can therefore not be subsumed in the logics of contrast or binary code that script visibility and invisibility, life and death. Simultaneously refusal and relation, Black feminist opacity is that which cannot be measured against, but requires to be in relation to. This is how it spreads forms of being that hack the script of subjectivity. This is how it enables life as lives.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to express her admiration for the work of Martine Syms, as well as her gratitude to the work of Dr. Katherine McKittrick, which has been influential in the writing of this essay, and to Dr. Tuck for making me understand it better. I would like to thank Yaniya Lee and Pamela Edmonds who trusted that the sharing of these thoughts is worth something, especially to Pamela for working through them with me.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to express her admiration for the work of Martine Syms, as well as her gratitude to the work of Dr. Katherine McKittrick, which has been influential in the writing of this essay, and to Dr. Tuck for making me understand it better. I would like to thank Yaniya Lee and Pamela Edmonds who trusted that the sharing of these thoughts is worth something, especially to Pamela for working through them with me.