You’re just a mass of images you’ve gotten to know

You’re just a mass of images you’ve gotten to know

from years and years of TV shows.

The hurting thing; the hidden pain

was written and bitten into your veins

I don’t and I won’t relate

and I think for some it’s too late!

—Ulysses JenkinsThank you to Aria Dean for her transcription of Jenkins’s Mass of Images (1978).

After a screening of his work, I heard the video artist Ulysses Jenkins say, “Rhythm is something that we all have.” He then turned to the title of his video work Inconsequential Doggereal (1981), explaining that he was interested in the idea of the doggerel, an irregular variation on a theme, sometimes in comedic verse. Jenkins is part of a group of Black independent media artists, including Tony Cokes and Lawrence Andrews, who have, since the 1970s and onwards, used broadcast media technology to conduct a kind of rhythmanalytic social critique, proceeding by way of an “ontology of vibrational force.”Steve Goodman, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012).

In Jenkins’s rhythm-conscious works, melody is substituted for a polyvocality that results from the inclusion of disparate vocal and visual samples from popular media, advertisements, and news clips alike. “For Bachelard,” Goodman continues in Sonic Warfare, “it was rhythm and not melody that formed the image of duration.” Black independent media artists, I argue, have an established history of producing these “images of duration” by working through subversive and rhythmic reappropriations of popular media material in the creation of avant-garde artworks.

In Jenkins’s rhythm-conscious works, melody is substituted for a polyvocality that results from the inclusion of disparate vocal and visual samples from popular media, advertisements, and news clips alike. “For Bachelard,” Goodman continues in Sonic Warfare, “it was rhythm and not melody that formed the image of duration.” Black independent media artists, I argue, have an established history of producing these “images of duration” by working through subversive and rhythmic reappropriations of popular media material in the creation of avant-garde artworks.

In “Written and Bitten: Ulysses Jenkins and the Non-Ontology of Blackness,” Aria Dean writes that, from 1978 to 1982, we see in Jenkins’s work

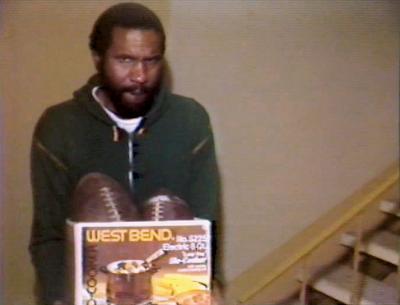

A reading through—or re-performance—of the original “text” of Jenkins’s video works provides a useful analysis of what Dean calls Jenkins’s investigation of “a non-ontological blackness.” Jenkins’s treatment of narrative, much like a non-treatment or anti-treatment of narrative, in Inconsequential Doggereal, formally enacts a social critique by way of a failure to produce a “legible,” or univocal, speaker. The video opens with a voice announcing the “forces of fire, water, and air.” The sound cuts. We see Jenkins sipping from a mug in a bathtub. In the next shot, he is lying on his back in the grass in front of an approaching lawn mower. Then, his naked ass bouncing onscreen. A woman crouching low to the ground in a nondescript room, her shoulder exposed as she tries to catch a football thrown to her from off-screen several times in a row. Continually, the video “gets stuck” and rewinds. Now, two people argue in a field. A star in a galaxy. Peter Sellers appears, followed by a brief clip from Jenkins’s Mass of Images (1978) where a sledgehammer rests in Jenkins’s lap as he wheels himself around a room full of televisions.

Ever interested in the materiality of the medium, Jenkins continually invokes the visual striations caused by the rewinding of VHS tapes in his images. These striations are a fairly consistent part of the Doggereal sequence, which moves forward, halts, and rewinds every few moments. They mark, in addition to movements through time, thematic slippages in the narrative structure of the video.

Later in Doggereal, Jenkins’s narrative interests seem to shift, almost imperceptibly, into romance. A football is being passed back and forth between Ulysses and a woman in a park. “Fuck you!” yells the woman. “You’ve done this to me so many times!” Scenes of horse racing are looped and repeated. A news reporter suggests that when people see one person commit a crime, others think they can do it, too.

Later in Doggereal, Jenkins’s narrative interests seem to shift, almost imperceptibly, into romance. A football is being passed back and forth between Ulysses and a woman in a park. “Fuck you!” yells the woman. “You’ve done this to me so many times!” Scenes of horse racing are looped and repeated. A news reporter suggests that when people see one person commit a crime, others think they can do it, too.

Jenkins jump-cuts between scenes of dysfunctional romance, and the commentary of reporters on TV cast Doggereal into a lyric on fraught race relations as a sort of failed partnering. “I don’t want you to be dependent on me!” implores a woman’s voice. “I want you but you don’t feel the same way.” She’s speaking to the character played by Jenkins. “I’m willing to give things up to be with you and learn about you,” she continues. “How could you not desire someone else’s love?” “You say you’re self-contained,” she concludes, and we see her face as it looks into the camera.

Jenkins’s character, who at the end of the video appears naked and is kneeling down in a foggy field of blowing dandelions, would seem to be woefully aloof, or aloft, not only unable to participate in intimacy for all his “self-containedness” but also, as it were, completely overwhelmed, from a narrative standpoint, by images of white romance and news documentation of minimum wage. Jenkins’s subjectivity exists at no fixed point in the video, and is instead cast into unstable positionalities of solitude and romantic ineptitude. This “failure to assert a legible ontology of himself,” as Dean writes, is what ultimately unfolds the narrative that Jenkins, at the same time, takes care to rhythmically construct.

As artists of the Black avant-garde have addressed for decades, images of Black people tell stories of Black people. Speaking on the circulation of photographs documenting the violence at the Columbia Avenue Riots on August 28–30, 1964, for example, Deanna Bowen writes,

Bowen’s performance at the Traces in the Dark (2015) exhibition at ICA Philadelphia featured the artist, accompanied by Martyna Majewski, re-enacting a 1964 interview between the KKK’s Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton and Paul Good, the author of The Trouble I've Seen: White Journalist/Black Movement.During his career as a journalist, Good interviewed the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., published in the New York Times, and, as a reporter for ABC News in 1964, he had visited Notasulga, Alabama, to investigate a school integration, where he would eventually sit down with Shelton. Margalit Fox, “Paul Good, 75, Television Reporter, Is Dead,” New York Times, February 7, 2005.During the performance, two microphones face in opposite directions at the centre of a gallery. An audio clip begins to play once Bowen and Majewski are each standing in front of a mic. In the audio clip, Good says that the Klan’s membership has reached over 8,000, and Shelton counters that the Klan doesn’t divulge exact membership numbers. The clip stops and Bowen and Majewski begin to read from their scripts.

Bowen’s performance at the Traces in the Dark (2015) exhibition at ICA Philadelphia featured the artist, accompanied by Martyna Majewski, re-enacting a 1964 interview between the KKK’s Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton and Paul Good, the author of The Trouble I've Seen: White Journalist/Black Movement.During his career as a journalist, Good interviewed the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., published in the New York Times, and, as a reporter for ABC News in 1964, he had visited Notasulga, Alabama, to investigate a school integration, where he would eventually sit down with Shelton. Margalit Fox, “Paul Good, 75, Television Reporter, Is Dead,” New York Times, February 7, 2005.During the performance, two microphones face in opposite directions at the centre of a gallery. An audio clip begins to play once Bowen and Majewski are each standing in front of a mic. In the audio clip, Good says that the Klan’s membership has reached over 8,000, and Shelton counters that the Klan doesn’t divulge exact membership numbers. The clip stops and Bowen and Majewski begin to read from their scripts.

Bowen approximates Shelton’s accent and cadence. “The organization is interested in maintaining segregation,” she says, finishing off a list of the Klan’s organizational interests with “welfare for the white race as well as for the Negro.” In response to Good’s charge that the Klan has a reputation of violence and bigotry, Shelton says, in Bowen’s voice, “The trouble with the news media is it doesn’t understand that the Klan today is different than in 1865. They are not a group of people who will allow communist conspiracy.”

The interbodily commingling inherent in Bowen’s re-performance is akin, in strategy, to Jenkins’s “dis-treatment” of narrative in Inconsequential Doggereal. In and through the re-performance, Bowen’s own physicality—in making way for the intrusion of Shelton’s ideology—signals another entryway into a non-ontological Blackness. When Good, articulated by Majewski, asks Shelton if he thinks the Negro civil rights movement is a communist conspiracy, Shelton launches into a tirade at the end of which he states that he should have, in his words, “choice of association.”

The interbodily commingling inherent in Bowen’s re-performance is akin, in strategy, to Jenkins’s “dis-treatment” of narrative in Inconsequential Doggereal. In and through the re-performance, Bowen’s own physicality—in making way for the intrusion of Shelton’s ideology—signals another entryway into a non-ontological Blackness. When Good, articulated by Majewski, asks Shelton if he thinks the Negro civil rights movement is a communist conspiracy, Shelton launches into a tirade at the end of which he states that he should have, in his words, “choice of association.”

Negroes are overvalued, he claims, given that they are responsible for more than 50 percent of crimes. How can they be a denied race when they are “on the shoulders of the white taxpayer?” he asks, almost coyly. Meanwhile, giving life to this particular instantiation of Shelton, Bowen and her surrogate embodiment of Shelton’s voice are the Klansmen’s total existence in the context of the performance.

There is only one other moment, besides the beginning, when the original interview recording is heard rather than orated by Bowen and Majewski. After Good has asked Shelton how the Klan will respond if Black militants pose a demonstration in the South this summer, and Shelton assures him that they would not “stand idly by it,” we hear Shelton––in his own voice––say that Dr. King Jr. has “finished his usefulness,” that the year would be one of violence, and that King would meet his end that year. He finishes by affirming the Klan as an educational platform, saying, “We can win our fight.”

The first two decades of the 2000s saw many Black contemporary artists, like Bowen, create complex critiques of the media, race relations, and the construction of historical narrative, suggesting a lineage of work by Black artists that challenges the mass media’s hegemonic control over social narrative. New, digital, and social media complicate this hegemonic control, but it's too easy to mistake consumers' more complex interactions with popular technologies with an increase in consumer power.David Morley, “Unanswered Questions in Audience Research,” Revista Da Associação Nacional Dos Programas De Pós-Graduação Em Comunicação, August 2006.

In Lineage for a Multiple-Monitor Workstation (2015), Sondra Perry complicates the idea of the power of the narrator to “direct” history. At the start of the video, a family in which everyone is wearing green masks poses for a picture. Perry’s voice, in the background, directs the family into their positions. They say “cheese” three times.

Shortly after, Perry pulls up two windows onscreen. There is only the faintest visual suggestion of a computer background. More windows appear and overlap, each of them, minus one YouTube window playing a Soundgarden song, carries the American flag somewhere in the larger image: the family, shown from different angles and vantages, folds the flag into triangles. Perry, in true avant-garde fashion, brings us to think anew about “old” things.

The music abruptly stops. Now most of the total image is given to a house’s exterior. Perry is directing again. She says, “It’s too act-y.” Together, Perry and her actor-subject negotiate a line of dialogue. She suggests saying something like, “How does it feel to be in a sweater?” She commands her mother to be herself. “Be regular,” she says.

Later on, the family is sitting at a table peeling yams, still singing in their pastel green ski masks. Some people in the room clap along with the song. “I’m so glad they prayed for me,” the song concludes. Perry is still facilitating the narrative. She addresses the room: “Try to connect with each other somehow without talking.” She apologizes for the instruction, which she calls esoteric. Not in a corny way, she says, but no talking.

One is stunned by the willingness of these family members to go along with Perry’s ardent vision throughout Lineage, which ends with an exchange of love that recalls Jenkins’s turn to romance in Inconsequential Doggereal. The turn to love and, at the same time, polyvocality is one basis of the “narrative unfolding” that marks the tradition of the Black avant-garde.

In In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (2003), Fred Moten asserts that the avant-garde is a Black thing and that Blackness is an avant-garde thing.Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).Given a growing body of artworks by Black media artists and an accompanying body of writing on those works, the need to articulate where exactly the Black avant-garde is propagating is important for Black artists resisting exploitation and depoliticization.

The contemporaneity of today’s media-arts technologies doesn't alone signal that the contemporary work being created with them is avant-garde, where avant-garde means both new and marginal to a hegemonic meaning-making framework. And again, given this history of media works within a traceable, if ineffable, Black aesthetic tradition and the body of their critical analysis, at least a portion of the work by Black contemporary artists that seeks opposition through “illegibility” has now become––or is at risk of becoming––hyperlegible in “sympathetic” white-dominated art spaces that do not otherwise stake a real claim in challenging a socio-racial hegemony.

In an interview in BOMB, Adam Pendleton says, “The avant-garde can put the body on the line—people tend to forget that. That’s why I often say that Rosa Parks was avant-garde.” Pendleton’s repoliticization of Parks’s protest strikes me as speaking to Cokes’s formulation of the Bus Boycott as a “product of fantasy” in Evil.27: Selma (2011/2017 refix). In typical Cokes form, Evil.27: Selma contains only text scrolling on- and off-screen, no “images.” The “textual speaker”Cokes provides the following citation for the video’s text during the end credits of Evil.27: Selma: Notes from Selma, August 2009. Our Literal Speed “On Non-Visibility.”suggests that the Bus Boycott was an “imaginative act” that concretized a possibility in the here and now.

Without an end goal, but merely a series of what ifs––what if we could ride the bus as equals, vote as equals, live as equals?––the movement collectively imagined what it was like to survive without transit. The underdocumentation of Parks’s actions, too, gives them a mythic quality resembling the overall “imagelessness” of the boycott. Images, the speaker asserts, may actually slow transformation, as they allow us to make something unfamiliar feel known. “An event that has no image will be of the imagination,” the screen reads. What is usually considered the weakness of social movements, it continues—that is, the lack of proof of “what is right”—makes the revolutionary undertaking more available.

Where Pendleton prioritizes the physical risk involved in protest—and equates that risk with the avant-garde—Cokes “disappears” the body that Pendleton brings to light and, not only that, says that the disappearance of that body is the basis of a necessary fantasy. Despite this difference, both Cokes and Pendleton instrumentalize Parks through an act of “revivification” in service of a present socio-artistic endeavor. Cokes’s and Pendleton’s parallel instrumentations of Parks suggest that not all those contemporary attempts to renew and repoliticize history are evidence of singular thinking.

Lineages and hegemonic meaning-making frameworks are maintained through performance, or "logics-in-use,"Stuart Hall, “Encoding, decoding,” in Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–79 (New York: Routledge in association with the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham, 1992), 128–38.rather than, for example, through the imbuing with meaning of discrete objects. This means that lineage is tracked not through a stasis of images, or kinds of image, or images of the same quality through time, but rather through the shared internal, performative thrust of the works that fall within that lineage.

Cultural theorists decoding the Black avant-garde to this day have interpreted these works as unilaterally oppositional, ignoring their contradictory and negotiated aspects, and through this, stagnating social discourse. Be that as it may, enough consistency within the Black contemporary arts in terms of “oppositional strategy” and performance signals the formation of a “local” hegemonic framework. In theorizing Black social artistic critique only as the performance of oppositional responses to a dominant hegemonic voice, we underprioritize the fact that negotiated and oppositional messages can also be encoded into media works,S. Ross, “The Encoding/Decoding Model Revisited,” (Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Boston, MA, May 25, 2011).rather than merely decoded, received, or interpreted.

During Lorraine O’Grady’s performance of her “alter-ego,” Mlle Bourgeoisie Noire, in 1980, wherein the artist appeared wearing “gown and cape of 360 white gloves”Ross.and carrying a whip with which she would occasionally lash herself, O’Grady recited the following poem:

THAT'S ENOUGH!

No more boot-licking...

No more ass-kissing...

No more buttering-up...

No more pos...turing

of super-ass...imilates...

BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!Ross.

The basis of O’Grady’s assertion that Black artists must take more risks is that they must do so to avoid the production of “art with white gloves on.”Ross.Ironically, works that take up O’Grady’s call are also doomed to interpretation against a white background, the basis of their opposition being a critique of white-dominated social establishments. These critiques rely upon the existence of white spheres of meaning for their own meaning, the meaning of their refusal.

What if, instead, we asserted that all Black art is, inherently, risky and discover what a critique of non-ontology itself looks like? By beginning with opposition as the primary text in response to which the avant-garde propagates, we open up the possibility for a newly non-ontological body of creative works. This approach, a kind of “communication after refusal,” decentralizes a white socio-racial meaning-making framework by naturalizing the idea of opposition, rather than marginalization. This then opens up for Black artists a new, “local” margin in which to propagate what has yet to be seen.